More readily available and affordable now than in the past, pearls still hold a special place in the hearts of many and their beauty is undeniable.

Freshwater and Saltwater Pearls

Natural and Cultured Pearls

Baroque Pearls

Baroque comes from the Portuguese barroco, meaning misshapen pearl. So a baroque pearl is simply a pearl that has no regular shape.

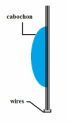

Nacre (NAY-ker)

Cyst Pearls and Blister Pearls

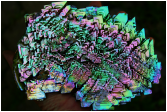

Non Nacreous Pearls

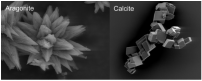

The calcite version doesn’t have the same light bending properties so it lacks the iridescence of the aragonite. It is dense, like thick porcelain.

The best of these pearls have a shimmering effect known as flame structure.

Conch (konk) pearls are produce by a large marine snail, the queen conch. The pearls are usually ovoid and small, ranging from white to a vibrant pink colour.

Some of the hardest pearls to find come from the marine baler snail, known as Melo Melo. The pearls from this mollusc are round, smooth and can be quite large.

Nacreous Pearls

Akoya

Akoya pearls have been grown off the coast of Japan for almost a century. That classic strand of white round pearls that everyone knows and loves? Those are probably akoya pearls.

Tahitian

South Sea

Freshwater

Pearl Grading

Imitation Pearls

One way to tell if your pearls are real or fake is to rub them across your teeth. Fake pearls will glide across, while real pearls feel gritty.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed